The Real 'Oakland Ilokana' Story: Lola Marie Rivera Yip and Elenita Makani O'Malley Heal Through Intergenerational Storytelling

by Jaeya Bayani

Elenita Makani O’Malley is a queer Filipina-Irish American filmmaker born and raised in the East Bay. In her day job, Elenita uses video to unpack complex narratives about the planet, the universe, and the tools scientists are developing to solve our world’s challenges. She’s worked for Stanford University, the American Museum of Natural History and more. Blending ancestral knowledge with two anthropology degrees, Elenita embeds community values at the core of her work.

Photo courtesy of @alyssamcorpuz.

In her next venture, Elenita will be diving into her first film, Oakland Ilokana. Three generations of Bay Area-born Filipina Americans – Lola Marie, her daughter Christine, and her granddaughter Elenita – lend their voices to an intergenerational tale about Filipino immigration, the women of the Manong Generation and generations since then. In this film, Elenita aims to question the dominant narrative of “who” a Fil-Am is expected to be.

Photo courtesy of @alyssamcorpuz.

Please introduce yourself, your craft, and the project you are working on.

“We’ve learned a little bit about the Manong Generation, but we are usually learning about men. This is an opportunity for us to see the world through a woman’s experience, too. ”

My name is Elenita Makani O'Malley. I am a filmmaker, and through the Balay Kreative Growth Artist Program, I am working on producing my first documentary film, Oakland Ilokana. It centers around the life of my grandmother, Marie Veronica Mendoza Rivera Yip. My Lola Marie was born in Oakland, California, in 1934, making her one of the oldest Filipino Americans ever born. In exploring her story, I'm examining about 100 years of Filipino American history, as well. In doing so, I'm hoping to expand our collective understanding of the Filipino American experience, as well as to question the dominant narrative of who a Fil-Am expected to be.

My Lola was part of the Manong Generation, named after the wave of young Filipino men who immigrated in the 1920s-30s, who were often called "manong,” meaning "elder brother" in the Ilokano language. What a lot of people don’t realize is there were some women here at that time, who would’ve been called manang or elder sister. At that time, there were probably 1 Filipina for every 15 men who immigrated to the country. My Lola and her mom were two of those women. My Lola's story gives us some insights into what it was like to be a young woman during that generation, when there were so few Filipina women. It's a story that's generally gone untold.

Can you talk a bit more about the specific intentions or inspiration behind your short documentary film, “Oakland Ilokana”?

“There are people who have walked this path before you, and especially during tumultuous times, it is critical to learn from the stories of our past. It’s not just a gift, but a responsibility. We have to steward our ancestors’ stories so the knowledge they carry can never be erased.”

So, my 90-year-old Lola was born in Oakland in 1934. She's second generation, she's a child of immigrants, but she's 90 years old. That's the experience that most Filipino Americans my age have now. Most Filipino Americans my age are second gen. They are children of immigrants, and there's a woman who's 90 years old who has this experience.

From a personal perspective, I wanted to understand how that's impacted my family as well. The year Lola was born was also the year that the Philippine Independence Act was signed, which began the process for the Philippines to become an independent nation for the first time in almost 400 years—which is a good thing. However, there was a side effect of that act: if you were a Filipino living in the United States when it was signed, you were reclassified as an “alien” overnight. You were no longer able to go back to the Philippines because you'd never be able to get back into the United States.

The year that my Lola was born, she was basically cut off from her ancestral homeland. So part of my inspiration for making this film was to understand how that impacted her, my mom's generation, and my generation, by extension. One impact of my Lola not being able to travel to the Philippines growing up is that she didn't travel to the Philippines until she was in her 50s. I'm the only other person in the family who's been to the Philippines, and I didn't go until I was 30. These are examples of the ripple effects that discriminatory legislation can have. They impact people for generations to come.

I've been trying to learn both how my generation can learn about our history, and the things that might have had ripple effects on us growing up and made us feel like we weren't as connected to our Filipino heritage. And it’s also to learn how other Filipino Americans, who aren't in my family, can learn from her experience that spans almost a century.

“It’s an interesting experience to film her playing mahjong with her friends after church on Sunday, and seeing 70-year-olds making sure that my 90-year-old Lola knows what they’re saying.”

What parallels, if any, do you see between second-generation folks today and your grandmother’s experience?

I definitely think there are similarities between my Lola's experience as a 90-year-old second generation Filipino, and Filipino Americans who are my age today. She doesn't speak any Filipino languages. She literally does not speak a word of Tagalog or Ilokano or any other language. All of her friends are 70-year-old Filipinos who moved to the United States in the 1970s. All of them speak Ilokano and all of them translate for her.

I think that can kind of echo the experience that a lot of second gen Fil-Ams feel today that are my age. Not everybody speaks their language. Lots of people are talking about, “Are they Filipino enough? Have they been to the Philippines? What is their connection to their cultural heritage?” Many of us are trying to reclaim or reforge those connections now. My path to doing that has been trying to understand where I come from, the people that I come from, and their stories. It's amazing to be educating each other in the spirit of Kapwa.

Has your grandmother expressed to you how meaningful it is for you to create this project about your life?

Yeah, I actually asked her the last time I interviewed her. My last question was, “What do you think about the fact that I'm doing this?” And I wasn't sure. She's a jokester, so I wasn’t sure if she’d brush it off or tell me I’d better make her a film star. But she surprised me. She was like, “I'm honored that you cared. I'm honored that you're interested in using your time this way.”

It's a lot of time, and we've spent hundreds of hours together this year, just dedicated to this film. I feel like she was honored to be heard, and I realized that it would be healing for me to hear her. I think that's part of what's driven me to work with her on this. There's a behind-the-scenes story that may not make it into the film, and I hope it's a story of healing for generations of my family.

How do you embody your identity as queer, Filipina-Irish woman and multi-generational upbringing in the Bay Area in your work as a filmmaker?

Photo courtesy of @alyssamcorpuz.

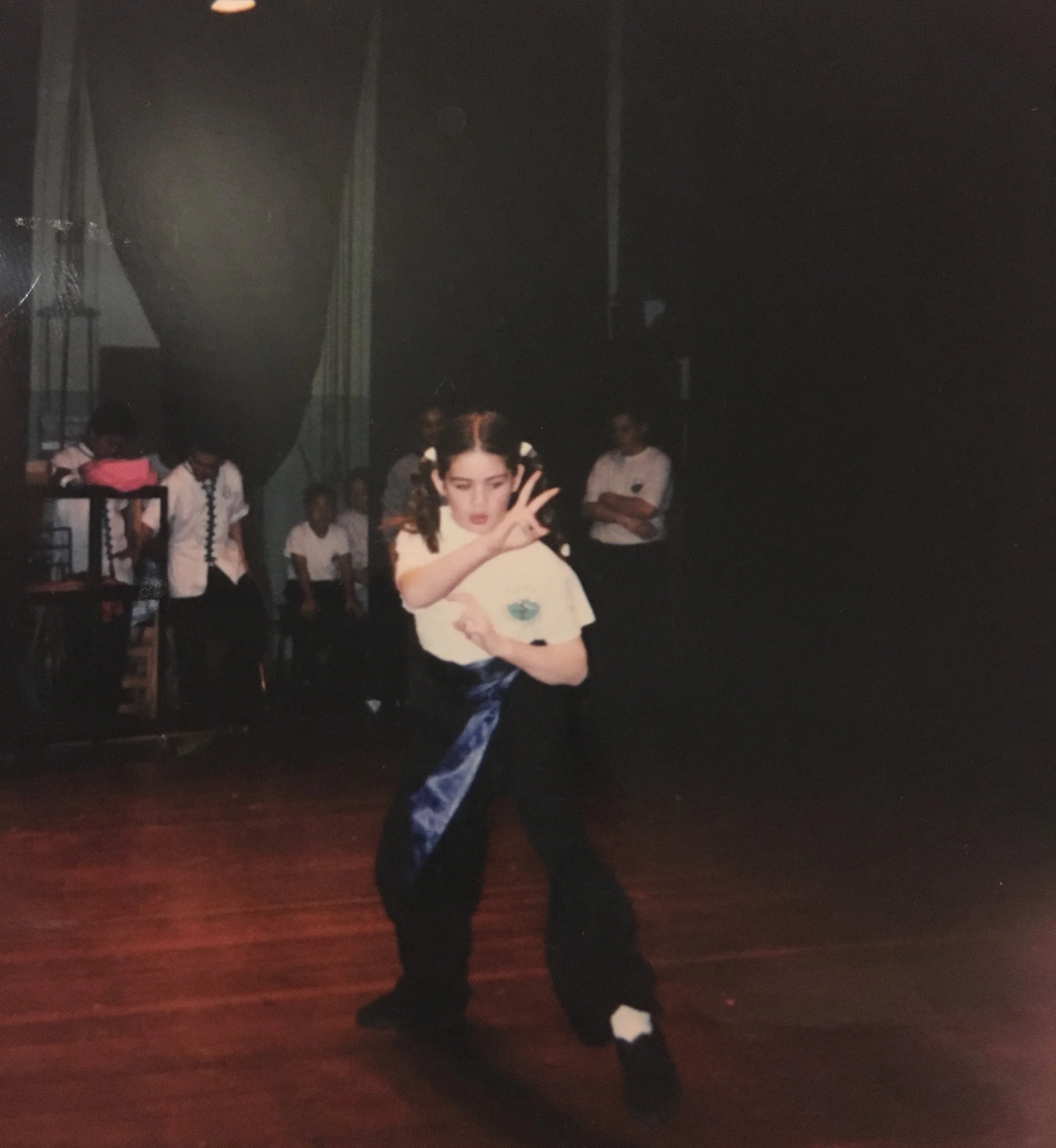

II think there are aspects of my identity woven into every part of this film. In doing that, I've also been weaving aspects of my Lola's identity, my mom's identity, and by extension, my other family members as well. I feel like this film has been a love letter to our family, our Filipino heritage, and growing up in the Bay Area. We filmed in the East Bay. We filmed in Oakland Chinatown a lot because my Lola was raised there. Growing up, I spent my whole childhood training in Kung Fu in the same neighborhood. I have lion danced at most businesses in Oakland Chinatown during Lunar New Year, too, so it felt special to be able to film in this place where we've all walked on this concrete. We all know this place.

We shot the rest of the film in Hawai’i. My Lola's dad immigrated first to Hawai’i, and he worked on pineapple/sugar plantations there. Since then, we have three generations of our family that all have really close ties to those islands. Hawai’i is a place that all of us have kind of made a placeholder for the Philippines. We didn't have the opportunity to go back to the Philippines, but we did go to Hawai’i a lot. It's a place where we've all found some sense of identity and belonging so I tried to weave that throughout this film, and find ways to highlight other aspects of our family's identity.

“When I was making this film, I knew I wanted to call it Oakland Ilokana if you break down the word “Ilokano,” it roughly translates to “from the bay.” ”

There are a lot of splashes of purple because it's my Lola's favorite color. I'm repping purple all the time now. I am trying to incorporate Bay Area hip hop because that's what I grew up listening to in the East Bay. Each scene has been lovingly crafted, not just by a director, but by a granddaughter. I think that it's kind of a patchwork of our experiences, and I'm hoping that it will also be a tribute to my Lola's legacy.

We're all born and raised in Oakland, California, and we're also three generations of people whose ancestors came from the Ilocos region. In two ways, we are “from the Bay.”

Why is it important for the next generation to advocate for the continued integration of our history and elders’ legacy through arts, culture, and ethnic studies into our local community?

Honestly, growing up, history did not click for me. I was an athlete, I was a martial artist, and I wanted to be outside. I really cared about embodied learning experiences, and history did not do that for me. I did not see myself in history. I did not see myself presented in history classes until I discovered anthropology and ethnic studies courses.

“I think it’s interesting that they call it ‘history’ when it’s about white/colonizer stories, but it’s called ‘ethnic studies’ or ‘anthropology’ when it’s about brown/colonized stories. ”

What do you think it does to a younger student to never learn about themselves in a history class, unless it's to learn that your ancestors were colonized, [subject to] genocide, or occupied? On the flip side of that, there's a real strength and there's a lot of confidence that can be imbued into a student to learn that these are your people, and that this is where you come from. For me, this film has represented an opportunity to learn about the people that I come from and what we're capable of.

Photos courtesy of @elenita.sampaguita.

I'm really interested in oral history and anthropology. Oral storytelling was our first form of learning and as humans, we’re literally wired to want to learn from other humans. We see that even on social media. Posts with faces are more popular because people want to hear from and learn from people. So I started to translate my storytelling into the video medium because that's how people consume oral storytelling today.

Most importantly, our stories need to be told by us. Growing up, I didn’t see my history reflected in school, which made my history feel irrelevant. But we need to give future generations the chance to learn about where they come from. If you don’t know where you come from, how could you know yourself?

Elenita & her mother, Photos courtesy of @elenita.sampaguita.

Is there any advice you have for your younger artistic self, and/or the next generation of Filipinx creatives, in writing?

Working on Oakland Ilokana with my grandmother and my mom has been a super meaningful experience. I sought out ancestral stories, looking for connection. I was looking for meaning, for patterns, and ultimately, I was looking for healing. I think there's a whole behind-the-scenes story of healing that's happening that won't necessarily make it into this film—but if there's one thing that I would like for viewers to take away from it, it's that you're Filipino enough, regardless of if you grew up in the diaspora, don't speak the language, if your parents tried to assimilate, if you are third culture, fourth generation, multiracial, or you have never been to the Philippines.

You are Filipino enough, and you have a Filipino story. And I, for one, would really like to hear it. It can be scary, vulnerable, nerve-wracking, and embarrassing to venture out and try to tell your own story; especially if you're not accustomed to telling your own story or being heard. It can be scary to dig in deep and try to bring that to people. In the process of making this film, there's a lot of things that I learned that I didn't necessarily want to learn. I've been working with my grandma and documenting her life history. I've learned all kinds of things that I didn't necessarily want to know, but I'm grateful for the experience. I'm grateful to be able to witness her story and to hear her say it herself.

There's a power in hearing people tell their own stories, especially when it comes from a place of vulnerability. If I was going to encourage anything, it's to trust your gut and don't be afraid to tell your own story. You never know when someone watching that film or who is reading that story is going to finally have that moment where everything clicks for them. You could be a catalyst in their life. You could change things for people who are watching your story so I encourage you to dig in deep, even if it's embarrassing.

Photo courtesy of @alyssamcorpuz.

What are your favorite emojis that you would use to describe today?

When I started this interview, I feel like the emojis I’d use to describe it are the sweaty face emoji 😓, throw up emoji 🤮, and poop emoji 💩. And I feel like now, I could just do the three sparkle emojis ✨✨✨. You are a great interviewer and I feel good now.

Photo courtesy of @alyssamcorpuz.

Do you have any announcements, updates, or goals relating to the process of Oakland Ilokana?

Shoot, things are changing everyday. By the time this is published we’ll be in a super different place than we are today. We're currently in production on my documentary film, Oakland Ilokana. I am featuring my Lola Marie. She's a 90-year-old Filipina-American born in Oakland, California in 1934. If you want to learn about 100 years of Filipino immigration history, I promise it'll be fun. This isn’t history class the way you’re used to it.

You can follow me @elenita.sampaguita on Instagram, my website, and the Oakland Ilokana page to stay in the loop!